OCaml at First Glance

You never get a second chance to make a first impression.

Lately I’ve been learning OCaml and I thought it might be a good time to share a few initial impressions, while they are still fresh. Of course, you should take those with a grain of salt, given that my knowledge of OCaml is still quite basic and I might be missing out on some stuff.

Also you should keep in mind my own background, experiences and preferences:

- Over the course of almost 20 years I’ve been programming professionally (mostly) in C, C++, Java, Scala and Ruby. The last 10 years have been almost exclusively dedicated to Ruby.

- I’ve always been super passionate about programming languages and on the side I’ve learned to some extent about a dozen more languages (e.g. several Lisps, Haskell, Erlang, etc)

- I’ve got a massive fondness for the simplicity of Lisps, I’ve written a ton of code in Emacs Lisp and Clojure, and I really love REPL-driven (interactive/incremental) programming.

- I’ve never been a strong proponent of either dynamically or statically typed programming languages. I’ve yet to see a compelling argument in favor of one side or the other.

Obviously, all of this tends to influence a lot my perception of (new) programming languages. That’s why throughout the article I’ll be drawing some comparisons to other (functional) programming languages that I’m familiar with.

General Notes

OCaml is a general-purpose, industrial-strength programming language with an emphasis on expressiveness and safety.

– ocaml.org

The language strikes a good balance between being functional and practical. In this sense it really reminds me of Clojure on the practical side and Haskell on the somewhat impractical side (the pursuit of purity comes at a cost). OCaml’s strict evaluation model makes it easier to reason than Haskell and also results in programs with more predictable performance.

Language Syntax

Language syntax is a favorite bike-shedding topic for most programmers, so I’ll do my best to stay constructive here. I think OCaml’s syntax won’t present much of a challenge for any seasoned programmer, especially for someone with a passing knowledge of a similar language like Haskell.

To put the discussion that follows in context, here are a few trivial OCaml code snippets:

let square x = x * x

square 5

(* a classic function definition *)

let hello name = print_endline ("Hello, " ^ name ^ "!")

hello "world"

(* filter a list with some predicate *)

let is_even x = x mod 2 = 0

List.filter is_even [1; 2; 3; 4; 5; 6; 7; 8; 9]

- : int list = [2; 4; 6; 8]

(* compute factorial recursively *)

let rec fact x =

if x <= 1 then 1 else x * fact (x - 1)

fact 10

(* reverse a list using pattern matching and tail recursion *)

let rev lst =

let rec rev' res = function

| [] -> res

| h :: t -> rev' (h :: res) t

in

rev' [] lst

I hope those snippets gave you some notion of OCaml’s syntax. I’ll admit that I’m fairly fond of it by now, although it definitely takes a bit of time to get used to it.

Things I Liked

Some aspects of the OCaml syntax that I liked:

- using

;;as expression terminator - that’s useful in toplevels as it makes it easy to input a multi-line expression. It’s also optional elsewhere, so it doesn’t add unneeded verbosity. - being explicit about recursive bindings. Notice the

reckeyword here:

let rec last = function

| [] -> None

| [ x ] -> Some x

| _ :: t -> last t

- type signatures are optional

- module types

- the ability to restrict an open module to a very small scope

let average x y =

let open Int64 in

(x + y) / of_int 2

let average x y =

Int64.((x + y) / of_int 2)

- labeled arguments

let div ~num ~denom = num / denom

div ~num:3 ~denom:10

- the ability to place the signature of a module in a dedicated

.mlifile. - the ability to have user-defined types that look as something built-in (e.g. lists,

refs, etc)

(* here's how you can define ref yourselves *)

type 'a ref = { mutable contents : 'a }

let ref x = { contents = x }

let (!) r = r.contents

let (:=) r x = r.contents <- x

- having handy functions like

|>out-of-the-box (I’m quite used to this from Clojure)

some_list |> List.filter is_even |> sum

By the way, there’s nothing really special about |>, it’s a function like any other. One of the nice aspects of OCaml’s syntax in general.

- the usages of

snake_caseinstead ofcamelCasemost of the time. I findsnake_caseidentifiers to be more readable, although obviously that’s super subjective.

Things I Disliked

Some aspects of the syntax that I disliked or found confusing (at least initially):

- using

(* *)for comments and lack of line comments (e.g.//is some C-like languages). Not the end of the world, but the comment syntax makes some things trickier (e.g. referring to the multiplication operator*) and is just too verbose.

(* this will work *)

List.fold_left (+) 0 [1;2;3;4;5]

(* this will work *)

List.fold_left ( * ) 1 [1;2;3;4;5]

(* this will not work *)

List.fold_left (*) 1 [1;2;3;4;5]

Here’s one more comment that won’t work - (* " *). I’ll leave to the curious reader to figure out why that’s the case.

- using

;heavily as element separator (e.g. in lists and records):

let some_list = [1; 2; 3; 4; 5]

You get used to this, but it’s a pretty big departure from the norm to use commas. I wonder what’s the reasoning behind this. Most likely it has to do with being able to define tuples without parentheses around them:

(1, 2, 3);;

(* - : int * int * int = (1, 2, 3) *)

1, 2, 3;;

(* - : int * int * int = (1, 2, 3) *)

(* a more realistic example of the usefulness of this *)

let a, b, c = 1, 2, 3 in

a + b + c

(* but we pay a steep price for the above convenience *)

[1, 2, 3];;

(* - : (int * int * int) list = [(1, 2, 3)] *)

- introducing multiple

letbindings is a bit too verbose for my taste - it took me a while to figure out the difference between

funandfunction - no syntax for list comprehensions (I often use those in Clojure, Haskell and Erlang, although I’m well aware they are not something essential)

- the syntax for array literals is somewhat weird (

[|1; 2; 3|]) - I don’t like such usage of multiple symbols as literal boundaries, as this makes it harder for dev tools to figure out what you’re doing. The indexing syntaxarr.(i)is slightly weird as well, as it doesn’t fit very well with the rest of the language. - no first-class syntax for maps and sets (Clojure spoiled on this front)

;; Clojure map

{:name "Bruce Wayne" :alias "Batman"}

;; Clojure set

#{1 2 3 4 5}

- nothing like Haskell’s typeclasses, which means in some cases you get different operators for similar types (e.g. numeric types):

(* int version *)

let average a b =

(a + b) / 2.0

(* float version *)

let average a b =

(a +. b) /. 2.0

On the bright side - it’s really easy to spot float operations.

By the way, this also means you get different operators for things like string and

list concatenation, as you can’t use + which is defined in terms of integers:

"Hello, " ^ "world!"

[1; 2] @ [3; 4]

Surprising Bits of Syntax

Here are some things that I like overall, but I found somewhat surprising early on:

- The

=operator is used both for assignment and for structural comparisons:

let x = 5

x = 5

- : bool = true

-

The operators

==and!=are used for identity comparison (whether you’re comparing something with itself), when in some other languages they are used for structural comparison. Not exactly wild, but not very common either. -

The operator for structural inequality is

<>. Although it’s not like Haskell’s\=is particularly common either.

By the way, when it comes to learning OCaml’s operators I can’t recommend this site highly enough!

- Several modules in the standard library have two versions - one where the functions are using positional arguments and one where the functions are taking labeled (named) arguments (e.g.

StringandStringLabels). Not exactly a syntax matter, but definitely a peculiarity.

# List.map;;

- : ('a -> 'b) -> 'a list -> 'b list = <fun>

# ListLabels.map;;

- : f:('a -> 'b) -> 'a list -> 'b list = <fun>

# String.sub;;

- : string -> int -> int -> string = <fun>

# StringLabels.sub;;

- : string -> pos:int -> len:int -> string = <fun>

- Having two ways to create anonymous functions - via

funandfunction. Basicallyfunctiononly allows for one argument, but allows for pattern matching, whilefunis the more general way to define a function.

let f = function x -> x * 5

let rec last = function

| [] -> None

| [ x ] -> Some x

| _ :: t -> last t

let f = fun x -> x * 5

let g = fun x y -> x * y

You can learn more about the differences between fun and function here.

Reason

Reason is a programming language powered by OCaml’s strong type system, and has a syntax designed to feel familiar to people coming from JavaScript or C-family languages.

– https://reasonml.github.io

In other words Reason allows you to leverage the OCaml ecosystem with a syntax that might be more familiar to some people. Think something like the relationship between Elixir and Erlang. Here’s some code written in Reason:

let launchMissile = () => {

someSideEffects();

print_endline("Missiles have been launched!");

};

launchMissile();

type schoolPerson = Teacher | Director | Student(string);

let greeting = person =>

switch (person) {

| Teacher => "Hey Professor!"

| Director => "Hello Director."

| Student("Richard") => "Still here Ricky?"

| Student(anyOtherName) => "Hey, " ++ anyOtherName ++ "."

};

Whether this is any better than OCaml’s syntax is up to you to decide. Personally, I’m not a fan of Reason, but if it helps grow the OCaml community then it’s a great idea in my book.

Syntax Summary

This too shall pass.

– Ancient Persian adage

Overall, there’s not much to write home about when it comes to OCaml’s syntax - it certainly won’t shock anyone the way Lisp or Prolog would. OCaml has a very long legacy as part of the ML-family of languages and I guess it accumulated a few syntactic oddities over time. I don’t expect any changes to happen and I got used to whatever I considered to be “weird” fairly quickly.

OCaml Platform (Compiler, Libraries, Frameworks)

In brief:

- the compiler is super fast, but that was expected given that OCaml is famous for it.

- the compiler is also quite helpful, although its messages can definitely be more descriptive in some cases.

- the standard library is quite basic and that’s probably my main gripe with the language so far - e.g. the support for things like string manipulation (the standard library doesn’t support Unicode strings) and regular expressions is abysmal given what you’d get with most other languages today.

- the above has spurred the creation of all sorts of extensions and replacements to the standard library, which creates a lot of learning overhead and fragmentation. I was amused to see that the popular book Real World OCaml directly recommends replacing the standard library with a third-party alternative.

- the package manager Opam is relatively easy to use, although using switches (isolated OCaml environments) takes a while to get used to. I’m still not sure that should be part of the responsibilities of a package manager, but it gets the job done. Opam could use some better documentation.

There’s also support to target JavaScript from OCaml sources, which looks interesting, but I haven’t tried it yet. ReScript (basically Reason that targets JavaScript) is also appealing in this space, even if it’s only tangentially connected to OCaml.1

One common complaint about OCaml is its lack of support for parallel programming - OCaml currently doesn’t natively support multiple OS-level OCaml threads running simultaneously. A global lock prevents multiple OCaml threads from running at once. The good news is that OCaml 5.0 is right around the corner and its flagship feature is native support for multicore parallelism! This article is a fantastic overview of Multicore OCaml. Exciting times ahead!

Back to the present - today OCaml has pretty decent support for concurrent programming (most notably via the library Lwt). Moreover, my experience with Ruby has taught me that one can get pretty far and build a lot of useful software despite the presence of a global lock. And don’t even get me started on the performance difference between Ruby and OCaml…

There are plenty of third-party OCaml libraries, although most of them seem somewhat under-maintained and under-documented. I’ve noticed that for many libraries all the documentation you’ll find is just API signatures - e.g. this.

The only framework I looked into was Dream (a web framework). It looked pretty nice, but it’s still in alpha, has only one developer and it seems he has been not been very active lately. Oh, well - that’s a common problem in smaller programming communities.

A Note About Standard Libraries

OCaml’s standard library has few fans and lots of competition.

It seems that today the most popular complete alternative of OCaml’s standard library is Base by Jane Street. There’s also Core which is a superset of Base and features even more functionality. As I’ve started out by reading the RWO book initially I was

using Base all the time, but I’ve stopped using it since. Not that the library is bad or anything - I just wanted to give myself some time to assess for myself the problems that Base supposedly solves, plus consider other alternatives.

I’ve recently discovered Containers, which extends OCaml’s standard library instead of replacing it completely. I plan to make heavier use of it going forward.

Development Tooling

I’d say the development tooling for OCaml is pretty decent, although I wouldn’t go as far as saying it’s great. I’ve documented my current Emacs setup here and I’ve also played a bit with the “official” VS Code extension to get a feel for OCaml-LSP.

Without a doubt, Merlin is the primary workhorse of the development tools and it’s definitely pretty awesome. It provides editor features like code completion, typing information, navigation to definition, refactoring, code generation, linting, etc. It’s a beast! Emacs’s merlin-mode reminds me in a way of CIDER (for Clojure).

utop is a good toplevel (REPL) and has become a major part of my OCaml toolbox. It’d be nice if down the road someone improves a bit the default ocaml toplevel, which is extremely basic by every modern standard.

Dune is a solid build tool and I definitely enjoyed working with it. It does need better documentation, though, as I learned more about it (and Opam) from third-party documentation instead of from their official documentation.

For testing I can recommend the following libraries:

- ppx_inline_test for simple tests that you can place alongside your code, while you’re developing it:

let is_prime = <magic>

let%test _ = is_prime 5

let%test _ = is_prime 7

let%test _ = not (is_prime 1)

let%test _ = not (is_prime 8)

- ppx_expect is a framework for writing tests in OCaml, similar to Cram. Expect-tests mimic the existing inline tests framework with the

let%expect_testconstruct. The body of an expect-test can contain output-generating code, interleaved with%expectextension expressions to denote the expected output:

open Core

let%expect_test "addition" =

printf "%d" (1 + 2);

[%expect {| 4 |}]

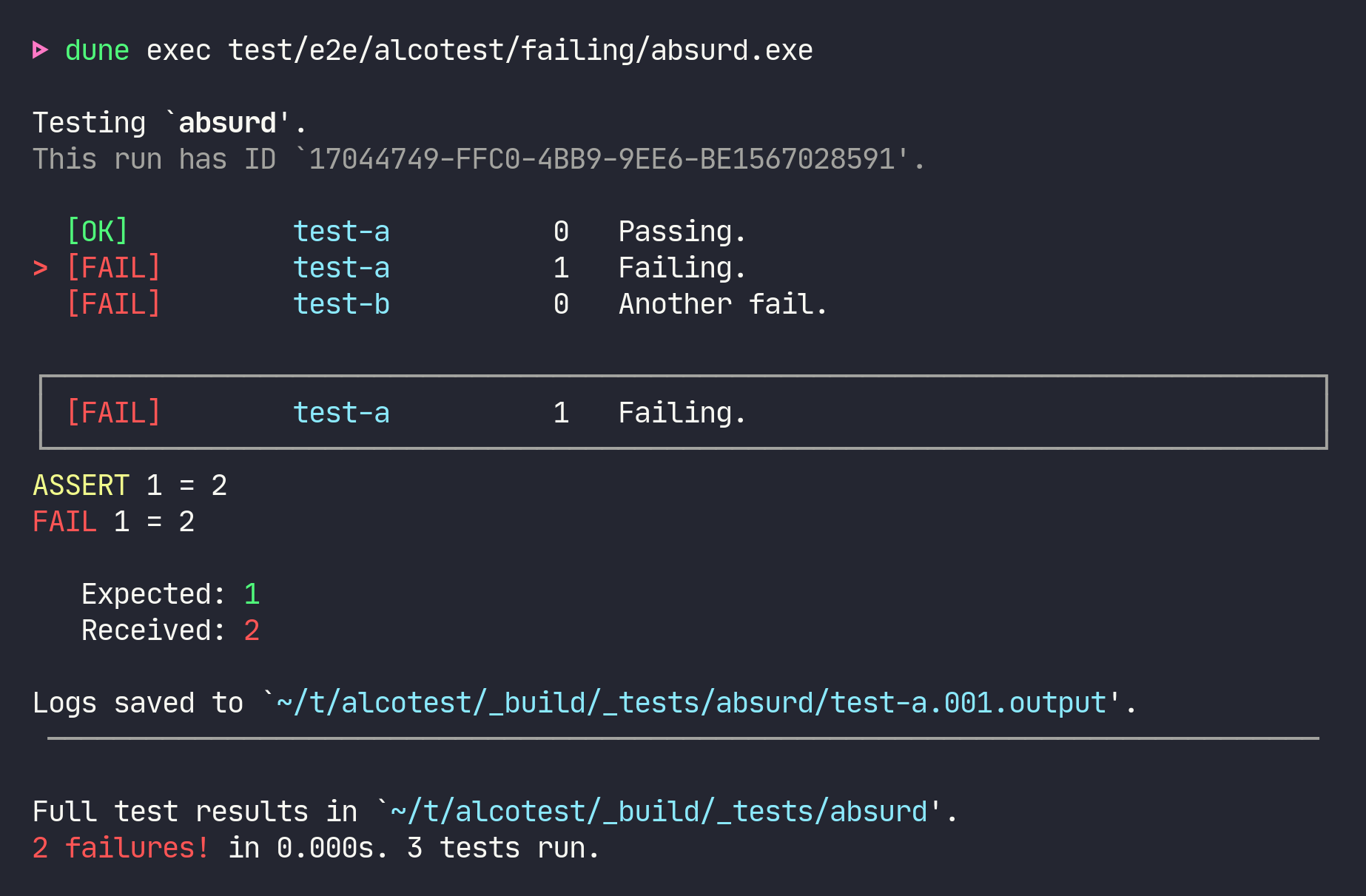

- alcotest is my favorite testing framework so far. It’s really easy to work with and it has beautiful output.

I think for most people a combination of VS Code + a utop and dune (e.g. dune runtest -w) running in dedicated terminals will provide the optimal development experience. This way you’ll be able to play with some small snippets of OCaml code in your toplevel and get instant feedback from your test suite on every change you make. Of course, if you can stomach Emacs - even better. ;-)

Community

The OCaml community is tiny by the standards of more popular programming languages, but I really enjoyed all my interactions with its members. I’ve been mostly using the official Discord and Discourse, but there are plenty of other options for you to chose form.

I’ve gotten plenty of answers to every question I asked and I really enjoyed learning more about the workflows OCaml developers have, as finding a productive workflow was one of the things I’ve struggled with early on.2

I also learned a lot simply be handing on there and perusing the topics that we being posted and channels like #general, #beginners and #share.

One final community resource I’d like to recommend is the awesome wiki OCamlverse. It complements really well the information on the official OCaml site.

Learning Resources

You certainly won’t find dozens of books, hundreds of tutorials and a few online courses for OCaml. It seems that the most popular resources to learn OCaml are:

- Real World OCaml: A free book about OCaml, that’s considered one of the best starting points in the community. On the flip side - it’s somewhat controversial for its decision to advocate the use of an alternative standard library (

Basefrom Jane Street). - Cornell University’s course on OCaml: It’s taught at the university, but the textbook and the video lectures are freely available online. I enjoyed the course, although it’s clearly geared towards students and not practicing programmers.

- OCamlverse: An OCaml community wiki. The articles there give you a lot of practical pointers about day-to-day OCaml programming and complement nice the tutorial/manual texts.

There’s also some tutorial-like section on the official site, but it could have been structured better in my opinion.

I definitely think there’s a lot of room for more resources for newcomers and that’s one area that will need work if OCaml is grow its mindshare. When everyone in the community is discussing the merits of a single book (RWO), you immediately figure out the problem is not the contents of the book, but rather the lack of alternative books.

While Clojure and Haskell are considered niche languages as well, there are a lot more learning resources of every flavor for them. I think that even Erlang has more resources than OCaml these days.

A Closing Note About Libraries

A while ago I made a comment about the standard library situation on Discourse that triggered a a follow-up conversation about two things:

- that the standard library wasn’t a major focus for OCaml’s team and they prefer for libraries to be developed independently by experts in a particular area (fair enough)

- that it’s actually easy to find the right libraries for each problem (it was mostly focused on strings)

While, I can agree with the first point in principle, I’d still expect at least a set of well-known libraries to be widely recommended, etc. Digging for libraries while learning a language is not always fun and sometimes leads in the wrong direction. On the second point - I was amused to see back-to-back comments that were contradicting one another. First I got the follow suggestion:

For example, for Unicode support you need to decide between Camomile and

uutf, depending on your needs.

And then it got this response:

I’m not sure I understand this comment. I don’t think there’s anything to decide between the two things you mention.

First the only thing that uutf provides, namely UTF codecs is nowaday available in

Stdlib.BufferandStdlib.String. Except if you rely on the non-blocking stuff, which most people don’t, there’s no reason to use uutf anymore. People should move away from it and consider it deprecated.Second if you need to access Unicode character data or perform normalisations, AFAIK Camomile has not updated its Unicode data for quite some time. Last time I looked it was Unicode 3.2 which was released in 2002, twenty years ago.

Since then thousands of characters, dozen of scripts and few new characters properties have been added. This makes Camomile entirely impractical to deal with the Unicode of today.

So I don’t think there’s any choice to be had here. You will be better served by

uucp,uunfanduuseg(this one not provided by Camomile).3

And finally the acknowledgment:

Exactly the kind of thing newcomers or casual users would absolutely never know unless they did a lot of research.

Indeed! Clearly finding the right libraries is not trivial in this case. Hopefully the situation will be improved with time.

Conclusion

I can’t say that my initial experience with OCaml was mind-blowing, but it was definitely pleasant and with time the language grows on me. I miss the simplicity and uniformity of Clojure (still my favorite programming language by far) or some of Haskell’s goodies (e.g. typeclasses, Hackage and ghci), but I feel OCaml strikes a very good balance between functional programming, pragmatism and performance.

At this point I’ve seen enough to be convinced to continue with my exploration of OCaml and dig deeper. Keep hacking!

You can discuss the article on Hacker News or OCaml’s Discourse.

-

This article covers well the confusing topic of how Reason, ReasonML and ReScript relate to one another. ↩

-

Pro tip -

dune runtest -w --no-bufferis essential! ↩ -

Don’t even get me started on names like

uucp,uundanduuseg. :-) Naming continues to be hard! ↩